In the following decade, will we really see the disappearance of single-mandate aid organisations?

As the aid community continues to ruminate upon the best way to meet the 21st century’s biggest challenges, we examine the feasibility of the ‘Nexus’ approach. Deemed by many as a boardroom pipedream, detached from the gritty, improvised realities of on-the-ground aid work, what can ACTED’s past experiences in Nexus programming tell us about the benefits of liberating aid work from the moorings of the humanitarian/development/peace divide?

What is the Nexus?

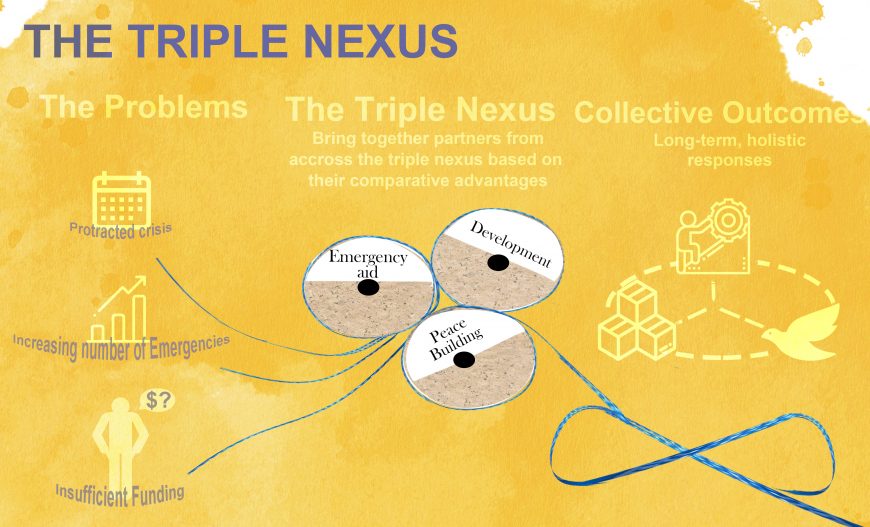

Despite its esoteric name, the ‘Nexus’ belies a very basic and largely accepted principle: that the conceptual and programmatic linkages between humanitarian work, development, and peacebuilding merit greater understanding in the name of facilitating holistic responses which integrate and capitalize upon these linkages. This is especially vital in the light of expensive, long-running, humanitarian crises (think DRC, Syria and Yemen), the impacts of which will be felt for decades to come. According to the UN-led reform process, the “New Way of Working (NWoW)” will mean actors are expected to work together towards collective outcomes which are achieved over a number of years, ensuring that humanitarian responses to protracted crisis make space for investments to achieved the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The UN's 'New Way of Working'

The Nexus approach is the outcome of a long series of UN-led engagements with the sector, which culminated in the so-called ‘New Way of Working’ (NWOW) outlined in a report entitled One Humanity, Shared Responsibility, released in the run-up to the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016.

The origins of the Nexus can be found in the concept of Linking relief, rehabilitation and development (LRRD), which emerged in the early 1990s and is described in this policy briefing. In agreement with many commentators from within the sector, the paper underlines LRRD as an ongoing development; something which has been developing over decades, but where implementation to date remains uncoordinated.

Know more

From one perspective, the Nexus is simply a way of dissolving the artificial divides which are the legacy of decades of NGO efforts to mark out defined specialisms, with hard walls erected between those focusing on development, humanitarian and peacebuilding operations. The responsibility for this trend is often placed at the feet of donors whose funding structures favoured organisations with clearly defined, often single-issue mandates with funding allotted on an annual basis.

Given the widespread acknowledgement within the aid community, that in real world situations, no one sector can or should exist in isolation, the community is questioning the logic of further embedding such artificial divides. To some the Nexus approach represents the most balanced response to this challenge, however, this point of view is far from universal…

What are the arguments for and against the Nexus?

Essentially, most questions coming from the more skeptical side of opinion center around the question of ‘How?’ As per a recent article in The New Humanitarian, ‘the nexus is easy to say, harder to deliver.’ Despite the perception that the approach is ‘nothing new,’ many commentators have raised concerns as to how the approach will be put into practice. There is also a question of ‘Who?’ i.e. who will determine what the triple nexus will look like for donors and who is really making the decisions in relation to its scope and intent? There is also a question as to who is responsible for implementing the nexus; humanitarian actors are sceptical of development actors, and vice versa. And both these actors are sceptical of the military which is most often the actor put into relation with the peace component of the triple nexus.

While the EU’s largest humanitarian aid body ECHO is supporting the EU’s piloting of the triple nexus in six countries, INGO staff at the most senior level have expressed the need for caution. The fear is that the need to engage with military forces, as intrinsic to the peace component of the Nexus, would compromise their capacity to deliver aid according to the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. To describe the problem in its simplest terms: There is a worry that interventions which have to achieve indicators linked to stabilisation and peace could see aid/investments syphoned away from those most in needs, towards alternative groups in the name of peacebuilding.

While there are many valid critiques of the Nexus approach, none of these arguments move us any further along in addressing the unavoidable questions which haunt the future of aid delivery. Another reason for this re-examination of aid strategy revolves around cost: Donor countries are paying more than ever. However, even as states invest in record volumes of aid, there remains a $15 billion gap in the annual global aid budget. This trend is fueled by the increasingly protracted nature of the target crises which show no signs of abating. With the average timeframe of displacement now at well over 17 years, a lot of ‘humanitarian aid’ is soaked up responding to the needs of those who remain locked in a state of crisis (i.e. requiring a first-line type response) for years on end. To get an idea of this, the average period of the ICRC’s engagement in response to conflicts is now 35 years. This arrangement simply reduces the amount of money available to the sector to respond to new crisis. According to a recent report by the Alliance 2015 consortium, ‘the reality is that funding for humanitarian action is being outstripped by growing needs, and more than 80% of humanitarian aid is now going to protracted crises.’

Within the sector itself, there is ample evidence of the shortcomings of the existing system: In brief, emergency aid deliveries are too short-term and limited in scope to address the scale of today’s major recurring crisis. As ‘emergency’ camps, set up in urgent interventions, remain embedded across DRC two decades after their establishment, it has become clear how displaced persons and host communities have lost their ability to cope outside of the emergency aid framework. If these responses had initially taken into account longer-term development considerations, such outcomes could have been avoided, lives saved, and money directed in a more meaningful direction.

The idea of the Nexus is to provide the programmatic framework, institutional support and funding to allow humanitarians to formulate their responses to protracted crises, while overseeing investment in development specifically targeted at helping a country meet the needs of the SDGs.

Equally, a lack of ‘conflict sensitivity’ among donor agencies may stem intrinsically from existing approaches which cannot help but favour certain territories or groups over others, leading to perceptions of prejudice and exacerbating tensions in the most fragile contexts.

In a recent DFID report, the authors underline the detrimental role of conflict upon both emergency and development program, they also point to how mistakes made by aid agencies in Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Nepal had forced the community to face up to some of the more uncomfortable implications of their work. In summary, examination of the adverse impacts of non-conflict sensitive aid projects in these countries included: 1) further entrenching war economies when aid was captured or manipulated by powerful groups, 2) exacerbating divisions between conflicting groups (for example between IDPs and host communities when IDPs are seen as receiving an unfair share of the response), and, 3) reinforcing the existing patterns of exclusion which may have been at the root of the conflict (especially when agencies restrict their work to only the more accessible areas).

While no one in the sector is oblivious to the complications of doing aid work in messy, complex and violent contexts and the less-than-perfect moral compromises which were necessary for life-saving work to continue, essentially the Nexus represents an opportunity to re-state the importance of Do No Harm principles. As the next section of this article explains, the Nexus also encourages implementing partners to mainstream peacebuilding activities/outcomes into their project frameworks, which means developing the necessary indicators and accepting responsibility for their achievement.

Taking all these factors into account, the justification for the Nexus system is well established, but how are the big players like donors, governments and NGOs encouraging the transition?

What could the Nexus look like?

While the question of ‘How do we get there?’ is yet to be answered, it is not so difficult to foresee the kinds of interventions, which could result. Once a needs assessment in an area identifies the roots of a food crisis, aid actors could begin a combined response which fuses emergency food distributions with initiatives to foster local agriculture which integrate soft components to reduce land conflicts between villages.

While this is only a theoretical example, ACTED has worked within a Nexus-style framework since its foundation in 1993, combining a wide variety of funding streams within each country context and rigorously observing an open, multi-sectoral approach. ACTED looks beyond the immediate emergency towards opportunities for longer-term livelihoods reconstruction and sustainable development.

The ‘Contiguum’: Combining emergency, rehabilitation and development approaches within the same time frame in a fixed area

While the ‘Nexus,’ is the universally-recognised label attached to the new dawn in aid strategizing which will do away with traditional emergency/development/peace divides, separate discussions at EU level have already given birth to a parallel vocabulary which appears to foreshadow the Nexus.

ACTED’s brand of Nexus-style programming is the ‘contiguum approach’: whereas the continuum approach, represents the traditional sequence of emergency aid operations, followed by separate processes of rehabilitation and development, the contiguum approach applies a parallel and simultaneous array of interventions falling across all three sectors, often funded by different aid instruments. After more than 25 years of LRRD programming, ACTED formalised its approach to operationalizing the NEXUS in fragile, crisis-affected areas by developing AGORA.

The AGORA approach consists of two pillars: synergies between local actors (local, provincial or national authorities, civil society) and external aid stakeholders and the use of settlements as the territorial unit for the planning, coordination and provision of aid and basic services. By doing so, AGORA not only improves the efficiency, relevance and effectiveness of humanitarian response but also promotes a more sustainable recovery of crisis-affected communities, providing a partnership and territorial framework that enables linkages between relief, rehabilitation and development action.

For a practical example of the contiguum approach in action, we can look to ACTED’s work in Afghanistan: Given ACTED’s long-term involvement in the province of Faryab in the north west of the country, few other organisations can boast such well-established relations with communities, nor such precise knowledge of the socio-economic space in which target communities live. ACTED is able to carry out parallel emergency/rehabilitation and development operations in Faryab through combining funds from emergency donors (ECHO, OFDA, etc.) with those from development actors, such as the World Bank and various national and international ministries.

Through focusing its assessments and subsequent actions at the level of Manteqas,[1] ACTED is able to understand both the capacity and needs of a given community to respond to emergencies and contribute to rehabilitation and development efforts. In Faryab, ACTED provides emergency cash response, transitional shelter construction and the rehabilitation of key water points. In terms of “stabilization”, in coordination with the Afghan government, ACTED has also implemented multi-year projects to support communities with the establishment of functional and accountable local governance mechanisms such as Community/Manteqa Development Committees (CDCs). CDCs represent an important stabilization tool, providing services with which all parties engaged in the conflict can agree on. Finally, in terms of development, through multi-year programming ACTED has supported rural households with the establishment of viable economic enterprises. These include improving agricultural production, through improved inputs and irrigation systems, or the creation of community base organizations and self-help groups to support the creation of small scale products (carpets, tailoring, computing, etc.).

While this manner of working has made the organisation rather an exception within a sector where the trend has been towards thematic specialisation, it has allowed ACTED to adapt dynamically to the shifting needs of communities as these change over time. This means providing the assistance people need rather than advocating for a particular thematic focus based on where the organisation feels most comfortable.

Over the past five years, ACTED has worked on a wide range of multi-sector projects traversing the emergency/development/peacebuilding divide in Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America.

[1] The Manteqa, is a fluid geographical/social area that shapes identify and solidarity in rural afghan communities. Rather than being a territorial unit, the Manteqa is a socio-economic space in which communities are active regarding their daily routines and which is structured by face-to-face social network relationships.

The Nexus in action in Iraq

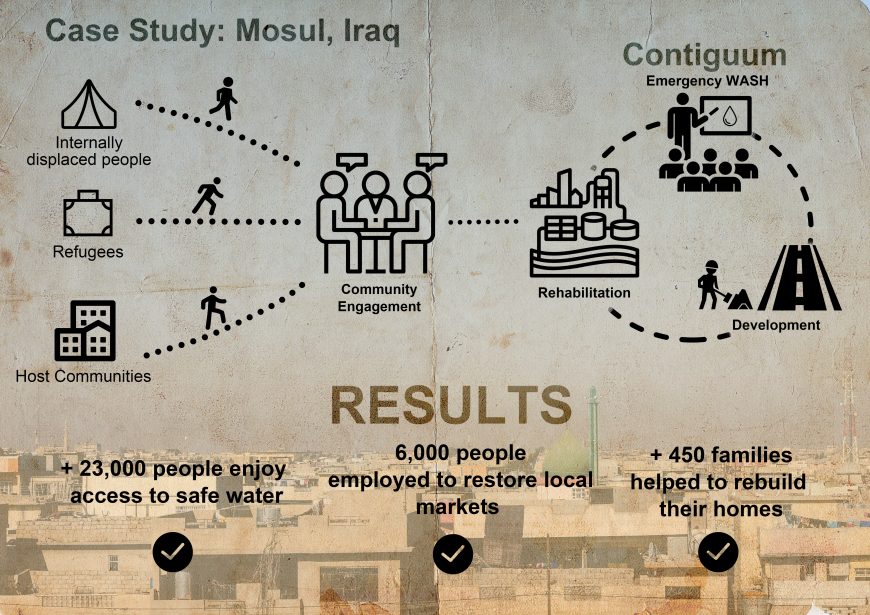

ACTED’s work in the Ninewa governorate in northern Iraq reflects an example of the Nexus in action.

Within the context of an intervention targeting both those returning to areas formerly under ISIL control, as well as IDPs, ACTED has applied an area-based, multi-sectoral approach to ensure the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance while supporting the transition to durable solutions.

In practice this meant designing a project which, although aimed at providing timely, life-saving actions, never lost sight of the need to incorporate long-term development considerations and conflict sensitivity (peacebuilding) into each aspect of the intervention. The latter is particularly vital in the target areas of Ninewa given how many of the factors which made these areas prime recruitment grounds for ISIL, which include failing rains forcing young men formerly employed in agriculture to take up arms for payment, are not yet resolved. Here we can see how the Nexus approach can contribute directly to preventing the re-escalation of conflicts which would create a new wave of long-term displacements and further protract the crisis phase of the aid intervention in Iraq.

The action incorporates a number of aspects and approaches which aim to make it conflict sensitive: A recent report by the Iraq Emergency Livelihoods and Social Cohesion & Cluster said ‘host communities that have a high proportion of residents who rely upon the government for basic needs are shown to be around 30 times more likely to have negative perceptions of and hostile relationships with IDPs.’ ACTED’s insistence upon shaping an intervention that targets the rehabilitation of communal infrastructure used by IDPs, returnees and host communities, represents a commitment to the kinds of fundamental ‘Do No Harm’ principles which must be integrated into any Nexus project.

As opposed to traditional approaches in which ACTED would assess the needs of several communities within a given area and then direct WASH assistance to water-starved areas, food assistance to drought-affected areas etc, within this action, the same beneficiary group is targeted within a continguum of assistance. While this may limit the total number of beneficiaries more so than the non-Nexus approach, it makes it less likely that those targeted through this intervention will simply rejoin the aid queue once the intervention is complete.

This area-based approach is widely implemented across ACTED missions for the following reason: The lives of individuals living within the target communities exist in a specific and complex matrix of relations shaped by a range of factors which include: levels of government investment/service provision, access to resources, relationships with surrounding communities, level of education etc, all of which determine their capacity to respond to the an emergency or development challenge. ACTED shapes its needs assessments to ensure that interventions take into account the geo-specific dynamics of a given target community, thus ensuring that the needs of vulnerable mixed population groups are comprehensively and effectively addressed.

The contiguum of assistance essentially incorporates three levels:

At the emergency level, ACTED provides hygiene promotion programs to minimize health risks from water borne disease in areas which are dealing with both large population influxes and poor WASH infrastructure provision.

At the rehabilitation/development levels, ACTED is rehabilitating community WASH infrastructure in urban areas, before handing these over to the relevant authorities as a means to ensure sustained access to quality WASH service. In urban areas, where large number of conflict-affected people reside, the rehabilitations of water networks will allow communities to rely on local water production systems to address their basic water and hygiene needs, decreasing the use of expensive and environmentally damaging water bottles and their overall dependence on humanitarian assistance. ACTED is also overseeing a shelter component which will give families locked in displacement the opportunity to break their connection with camp/informal settlement-based assistance and reintegrate back into their home communities.

To address the economic factors which leave Iraqis dependent on aid assistance, more vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups and disincentivise returns, ACTED is also rehabilitating sites selected on the basis of those which will have the greatest impact on generating employment opportunities. This also involves restoring access to markets by rehabilitating prominent access roads.

In relation to peacebuilding and social cohesion, early on ACTED noted how this third aspect of the Nexus was being overlooked in the broad response to the situation in northern Iraq, particularly around Telafar and Mosul. Given the aforementioned challenges and sensitivities, ACTED has taken a number of steps to ensure programming upholds ‘Do no harm’ principles.’ In addition, the newly established Community Resource Centers allow a space in which the organisation can deliver a range of educational sessions which integrate awareness raising sessions on social cohesion with CV writing workshops and English language courses. These measures, in addition to targeting the rehabilitation of public infrastructures which serve ALL groups in the community, represent crucial and impactful ways in which to help Iraqi society reduce tensions and rebuild its internal relationships.