As Northeast India makes up only 4% of India’s population, this remote and isolated region is notoriously excluded from both policy making and welfare programmes. In the hope of improving this situation in a mostly rural and poor area, the Indian government implemented specific schemes to improve access to basic services regarding health, education or housing. Yet these schemes are often obscure to the people who live there, especially since they speak a different language from the rest of the country.

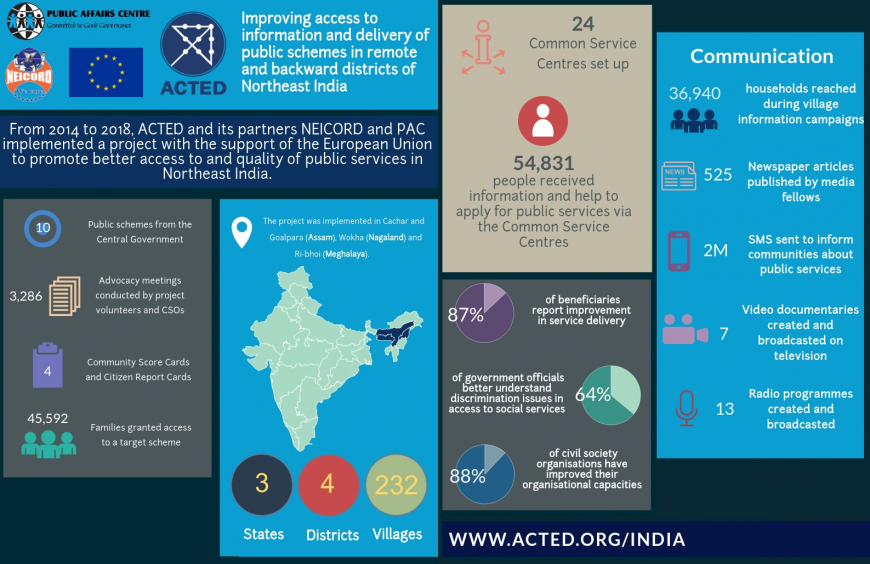

As ACTED and its partners NEICORD and PAC are now closing a four-year project supported by the EU to remedy to this issue, we take a look back to see what the project has achieved and what remains to be done.

Bridging the communication gap for better access to public services

In order to raise awareness about public services (such as a scheme that enables pregnant women to give birth in government hospitals free of charge, and provides free healthcare for new-borns), a mass information campaign was organised. Its approach focused on mixing media to reach a diverse and large audience.

Twenty TV and radio programmes were developed and broadcasted to disseminate useful information about the target services. Another twenty fellowships were offered to local journalists for publishing articles to inform local communities of their social rights, and so 525 articles were published during the project period. But there were also less conventional approaches, as text messages alerts on schemes were also set up, with two million SMS sent during the project. Furthermore, three village information campaigns reached more than 36,000 families across four districts of Northeast India.

Lastly, 24 local businesses, mostly Internet cafés or stationery shops, were given a grant to be used for purchasing computers and other IT equipment to become Common Service Centres and provide services like IT courses. They are meant to be essential community resource points to relay information about public services: information on what people are entitled to, procedures and the offices to go to when applying to the schemes, as well as access to e-grievance facilities, are made available to all by these centres. One of the centres’ owners, Anika, says she has helped more than 700 people register online to get a teaching diploma, helped new voters register online, students apply online for scholarships… All in all, about a hundred people come each day to her centre.

Beneficiaries advocate for better quality of public services

Besides raising awareness, ACTED also strived to address the issue of service quality and give a voice to service users. This was done through social accountability tools such as the Community Score Card (CSC), meant to assess public service delivery. During a CSC, both service providers and users score service quality, in separate focus groups, followed by a joint, collective analysis and discussion during face-to-face meetings. This provides a platform for direct advocacy by the communities.

For example, during one of these joint meetings, beneficiaries mentioned the lack of doctors, and as a result local authorities agreed to advocate the state for the immediate filling of vacant positions. Promises were fulfilled, and it was found at the end of the project that users’ satisfaction regarding availability of doctors increased by 60%. Overall, nearly 90% of the participants reported an improvement in the quality of the services between the beginning and the end of the project.

The way forward

Despite the progress made, much remains to be done to ensure that all eligible people benefit from public services, as discussion with communities and civil society organisations should continue to improve access to services for women, minority groups, and people with disabilities. The communities of Northeast India need to be continuously engaged both by NGOs and government authorities in the feedback processes to demand efficient service delivery. Moving forward, further space for beneficiaries to share their issues and concerns with public service delivery should be focused upon.

As the project now ends, it is essential to build on and continue this momentum to ensure the long-term sustainability of this intervention.

Beyond the project period, local NGOs trained by ACTED and its partners will continue to advocate for improvement in service delivery and better access to public schemes. Indeed, one of the community leaders who participated in the project, Sita, thinks that:

If the people come to know about their rights, the issue of underdevelopment will certainly take a back seat.